Interview with Jeff Durney, Ambulatory Human Factors Specialist

Jun 7, 2018

Jeff Durney started his career as a pilot. As a little kid, he used to pull magazine and newspaper articles about plane crashes. He was really interested in the training and procedures that went into these complex machines, airplanes. He didn’t have a name for what he was interested in at the time, but he later realized that his passion was in human factors engineering.

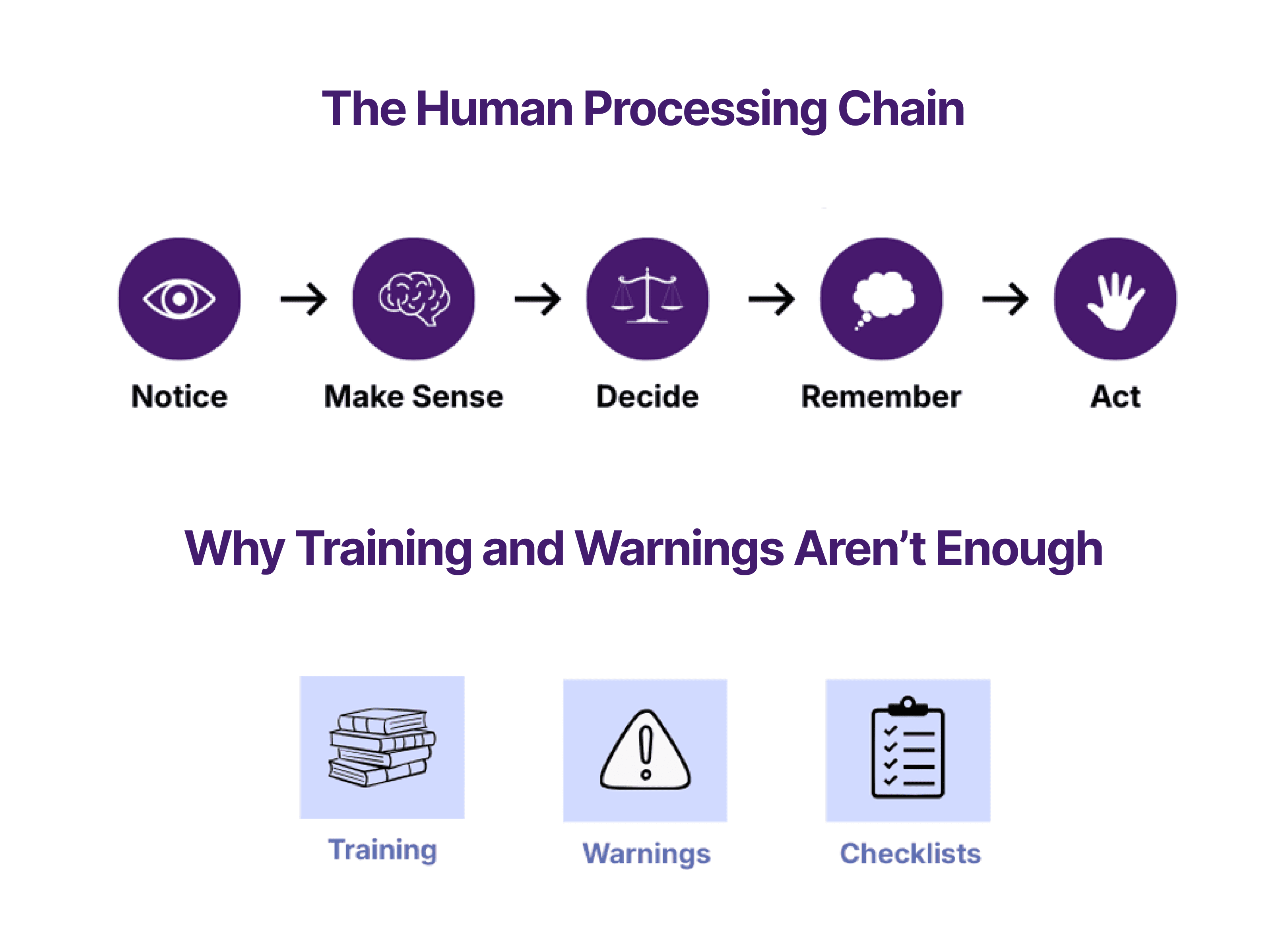

Over time, Jeff realized that in many ambulatory surgery facilities mandated the use of a safety checklist. However, when a checklist is merely mandated, people will do the minimum required to “check the box.” He realized that people were filling out these checklists but not truly making use of this tool.

Jeff read the “Checklist Manifesto” as he was further exploring human factors in the medical field. He thought, 'maybe this is my second career,' and transitioned into the healthcare industry. He worked for hospitals in Boston until Atul “caught wind” that there was a pilot working in the healthcare system advocating for human factors. Jeff ended up working with Atul Gawande for 3 years helping people implement the surgical safety checklist the right way. Jeff was striving to turn that piece of paper hanging on the wall into an integral part of the culture. Atul was looking for someone who had experience using these types of tools. Pilots use checklists in the proper way and “it’s unthinkable to not have that happen” but healthcare professionals don’t get a lot of training on how to use these checklists.

Jeff noted that when you’re talking about these concepts, it is good to keep in mind that the pilot goes down with the ship. Mistakes are both fatal to the passengers and pilot. Surgeons do not face the same level of fear pilots do. That’s not to say that surgeons don’t face consequences- there is the potential damage to their career, the emotional impact of losing a patient, among other things. However, in the end, if a surgeon makes a mistake that leads to patient death, the surgeon still gets to go home at the end of the day.

Jeff observed that part of the problem with proper implementation of the checklist may be in the way that surgeons are trained. When they come up through medical school, they have all those years of education, slowly grooming them over time to be the captain of the operating room. They’re trained to be the captain or the professional in the room and not look to “crutches” for help. There’s a level of vulnerability; they can’t know everything in any given moment. A tool like a checklist “can pull that information out of the team and make it available to the surgeon.”

The surgeon safety checklist has evolved over the years. One of the things that Jeff’s team added was a “search and statement” at the “point of no return.” This is the final check before the surgeon starts to cut. We put a statement in the checklist that says, “Does anybody have any concerns? If anything concerns you during this case, please speak up.” Jeff explained that this is “difficult, culturally speaking, for surgeons to say.” There have been cases where they were about to cut into the wrong finger or the wrong arm, and the OR staff didn’t speak up. We added that checklist item to allow people open up.

The iPhone may be the most intuitive device that anyone can use. In the absence of that, Jeff noted that in-depth training is needed. One thing that we don’t do enough of in healthcare is recurrent training. We do a pretty good job of training them upfront, but we don’t come back often enough to assess their skills at regular intervals. Pilots go through initial training but they also refresh that training with a simulator every 6 months. You don’t get to go back to flying passengers until you’ve demonstrated that you can handle emergencies.

During the initial training on a new procedure or device, Jeff once asked, “it’s great that you’re signing folks off on real experience in a simulator, but do you assess their skills and prevent them from working with real patients unless they demonstrate they could do their job on a simulator?” The surgeons reacted with surprise about putting their jobs on the line in such a way. Jeff noted that this is what pilots do, they put their jobs on the line.

It is incredibly expensive to take pilots out and put them through skill refreshers, but the airlines realize that it’s a necessary step. In a similar way, in healthcare, if you have a problem anesthesiologist, and these issues don’t surface in a simulator environment; there are huge ramifications including damage to the reputation of the institution, patient outcomes, etc. It is a balancing act; it is expensive to do these things, but it is also expensive not to.

There’s a move now in healthcare towards focusing on outcomes. There is talk of “non-payment” for bad outcomes. Also, there have always been lawsuits associated with injuries in the hospital. If a patient comes in for a certain condition, but they have to come back for re-admission, payers might not pay for the return episode. The hospital sent the person out and so they should have received the appropriate care and should not need to come back to the hospital for the problem.

In the airline world, we talk about the value of safety reporting, where pilots are incentivized to report anything that happens which is out of the ordinary. Such safety reporting processes remove the reporter in terms of liability. In the clinical space, this type of reporting is often avoided because such reporting may result in punishment or blame being set on an individual or organization. When reporting safety critical events, the organization may be legally vulnerable if the concern is not mitigated in a timely manner. Such instances may become a legal nightmare unless laws are put in place which allow anonymity and make certain that some reporting details are left non-discoverable.

If the healthcare industry was able to adopt the same “let’s share what happened” position as the aviation industry, then safety related issues would be reported and addressed to reduce to occurrence of safety issues. At the law-making level, we need to make certain things not discoverable to protect users doing these things in good faith. Removing the risk of retaliation from medical safety reporting will improve the quality of our data and of patient care.