How My Breast Cancer Journey Made Me a Better Human Factors Engineer

Oct 2, 2025

My breast cancer diagnosis was a shock. It temporarily devastated me and my family, but once the initial shock settled (and we knew it was treatable), it became more than just a medical issue; it was educational, particularly in respect to interacting with medical technology and the emotional impact it can have.

I work as a Human Factors Engineer specialising in medical devices and dedicate a lot of time understanding users and their needs, but the experience of breast cancer has made me a more empathetic and effective practitioner, and more determined to ensure products are safe and simple to use for those experiencing some of the worst times of their lives.

Before my diagnosis, I focused on optimising user interfaces and minimising errors. I understood the importance of ensuring devices and treatments fit into the lives of the patients, but I hadn't personally experienced why it was important and the impact that treatments and product designs can have. Throughout my treatment, I became the "user" of some products as well as a patient and the impact and emotional turmoil associated with having a serious illness, affected not only the use of medical devices, but everyday products too.

Key changes I experienced as a result of cancer treatment (both medicinal and surgical) included:

Physical Limitations: Chemotherapy and surgery brought fatigue, aches and pains, and seriously slowed responses. Minor design flaws can become major barriers when physical capabilities are compromised. Even getting comfortable following surgery is difficult when you have multiple dressings, drains and pain to contend with.

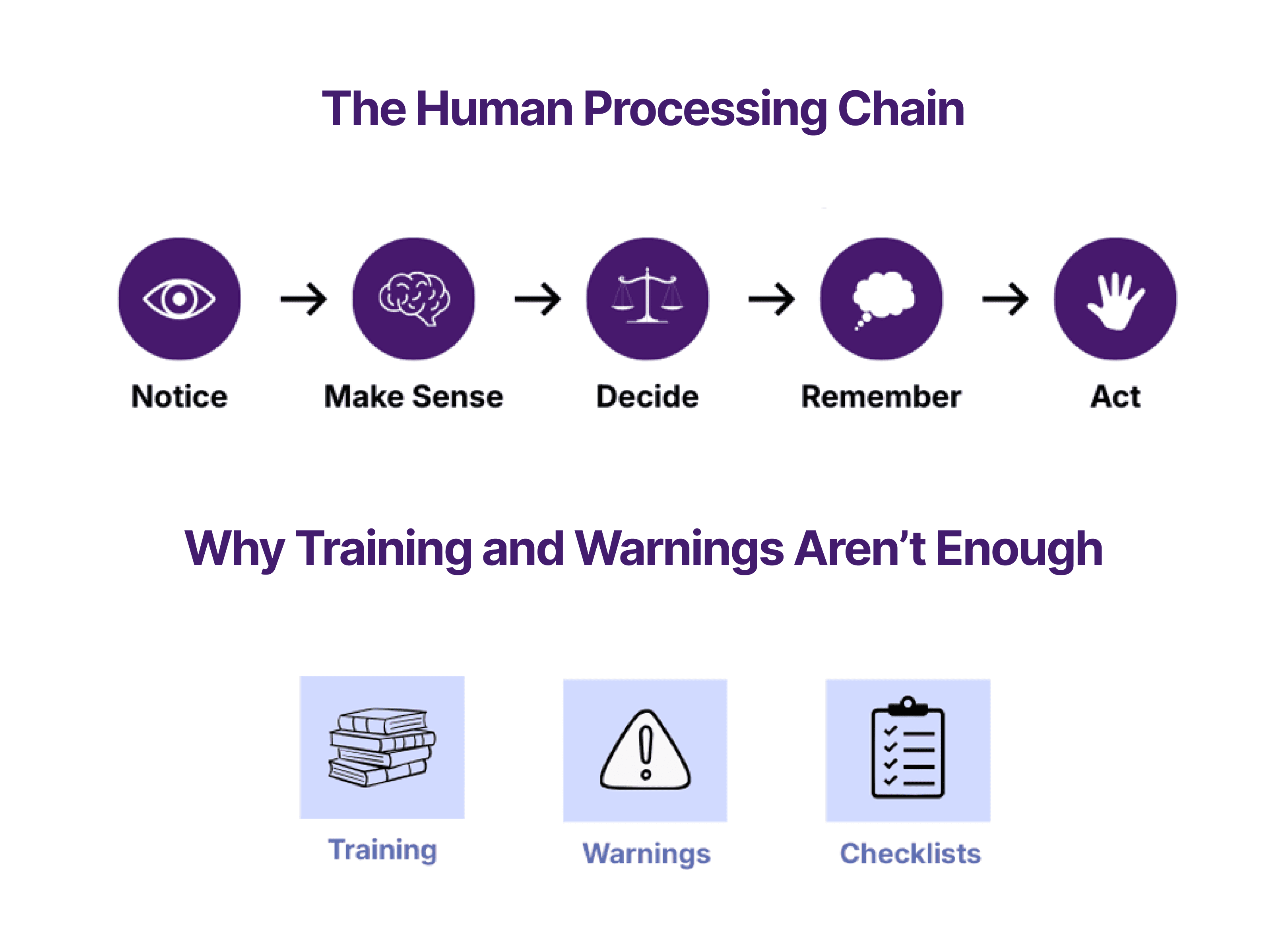

Cognitive Overload: "Chemo brain" is real. Processing complex instructions became much more difficult. Unclear labelling or convoluted workflows were incredibly frustrating. I realised the need for simplicity and clarity, especially when patients are under stress and experiencing cognitive impairment. I also experienced situations where I carried out activities twice with no memory of doing so and sometimes missed things altogether.

Emotional Vulnerability: Fear, anxiety, and uncertainty permeated every aspect of my treatment. Added to this are the changes to physical appearance which many experience, in my case hair loss and permanent changes due to surgery. Dealing with treatments while emotionally overwhelmed highlighted the importance of designs that inspire confidence and reduce anxiety. This is also applicable for those around us, significant others/carers become equally overwhelmed whilst also trying to ‘carry on as normal’. Interestingly, despite all of the medical attention I received I felt increasingly isolated, friends want to be supportive but struggle to know what to say and contact decreased throughout treatment.

Context Matters: Treatment wasn't confined to a sterile clinic. I used devices and medications at home too. This experience underscored the importance of designing for diverse environments and considering the full patient journey, not just the clinical setting.

The Human factors part of my brain is always looking for opportunities to make the most of my experience and as a patient/ user it's easy to identify where things can be improved (big shout out for more early stage research/insights to establish a deep understanding of user needs and requirements at the start of projects).

And my personal experience significantly improved my focus on some key Human Factors aspects.

Increased Empathy: I now approach every project with an even deeper understanding of a patient's perspective. I don't just consider the "average user"; I consider the individual facing a medical challenge, with all their unique limitations and anxieties.

Accessibility: My experience with physical and cognitive limitations has made me advocate more strongly for accessibility. I now prioritise designing devices that are usable by individuals with a wide range of abilities.

Emotional Design: I recognise the power of design to have an impact on emotions and work towards ensuring device user interfaces are not only functional but also comforting and reassuring.

Real-World Testing: I ensure that usability studies are carried out in representative environments, including home settings, because it’s important that a device is usable in the real world.

Clear Communication: My experiences with confusing instructions and medical jargon have made me more aware of the need for clear and concise communication.

The Whole System Matters: It is not just the device but the whole system around it. The instructions, the packaging, the support, and the environment that the device is in, all play a role in the users' experience.

Being affected by breast cancer has given me a renewed sense of purpose. I am now even more driven to ensure that medical devices are not only safe and effective but also truly user centred. I believe that by incorporating the patient's perspective into the design process, we can create technology that empowers individuals and improves their quality of life.

My journey has shown me that Human Factors Engineering is more than just a technical discipline; it's about understanding and respecting the human experience. And that sometimes, the most valuable lessons come from the most challenging experiences.